| White Paper: Nursing Home Staffing |

|

Introduction CALTCM is the medical voice for long term care in California. Our public policy committee developed this White Paper with the intention of making recommendations based on evidence-based literature. CALTCM’s Board of Directors approved this White Paper. It was not our intention to debate the financial impact of our recommendations or where nursing staff will come from, given the current huge workforce shortage issues. We stand for quality care in nursing homes. We absolutely understand many of the issues that have put nursing home care in the precarious state that the COVID-19 pandemic has tragically highlighted. Those issues need to be debated and those problems addressed, but that does not change the existing evidence. Our White Paper presents the evidence. We’re ready and willing to have a debate over the evidence, though we think it’s more important to have a vigorous discussion on how to finance these recommendations and find the nurses and nursing assistants needed to fulfill these requirements. California’s nursing home residents have faced an ongoing humanitarian crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing home residents constitute less than one percent of the population but account for a wildly disproportionate percent of California deaths from COVID-19. They are also human beings who deserve to be treated with respect and dignity. Surely no reasonable person could seriously dispute that. These are our recommendations:

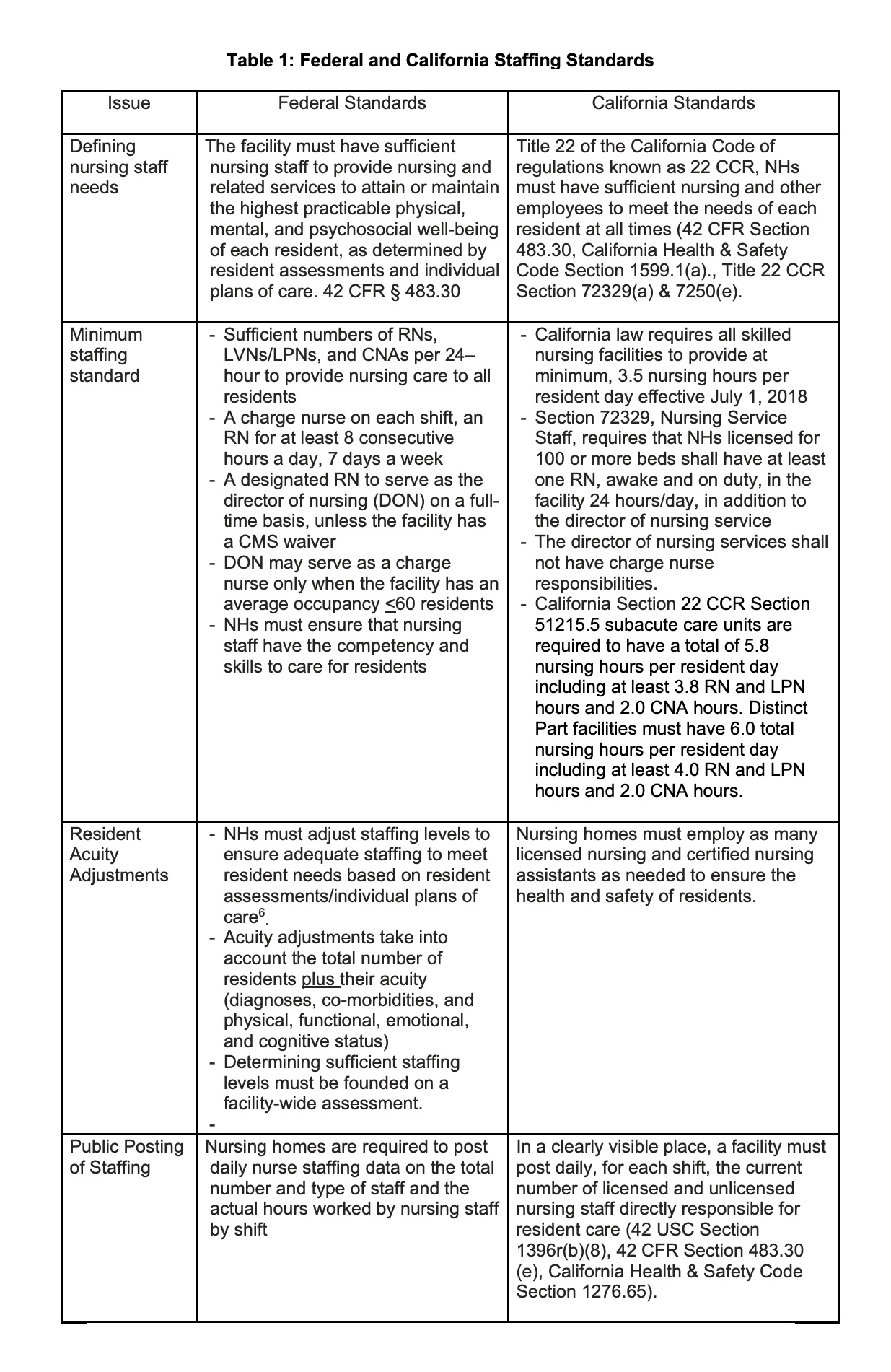

You may hear critiques of the studies we referenced. Ask for specifics. We’re more than happy to have an open debate on this important topic. We understand that there’s always value in more studies to further clarify and focus our precise definitions of minimum staffing levels. Unfortunately, nursing home residents, and the quality care they deserve, cannot wait for such studies. Let’s immediately start discussing how we can bring our recommendations to fruition. The time for action is now. Download White Paper on Nursing Home StaffingCALTCM White Paper: Nursing Home Staffing Overview The COVID-19 pandemic has brought attention to pre-existing quality issues and inequities and disparities that exist in nursing homes across the country. Multiple research studies have shown a positive relationship between the quality of nursing home care and staffing, especially for certified nursing assistants (CNAs) and registered nurses (RNs), but also for total nurse staffing. Prior to the pandemic, low nurse staffing levels were known to be associated with poor quality of care as well as abuse and neglect.1 The impact of disparities in nursing homes was also evident before the pandemic.2,3 Racial and ethnic minorities tend to reside in nursing homes with limited financial resources, low staffing levels and a high number of deficiencies.4,5,6 One study showed that only 9% of White nursing home residents live in “lower-tier” homes, compared to an estimated 40% of Black nursing home residents.7 A recent study found that nursing homes with the highest proportions of non-White residents experienced COVID-19 death counts that were 3.3-fold higher than those in facilities with the highest proportions of White residents.8 There is ample evidence-based literature documenting negative outcomes during the pandemic related to disparities.9,10 Now is not the time for additional “studies” to assess the importance of appropriate staffing levels. The combination of inadequate staffing and disparities can only lead to more tragic situations and outcomes, such as those recently seen during the latest hurricane in Louisiana.11 California’s nursing home residents have faced an ongoing humanitarian crisis with over 60,000 resident COVID-19 infections and almost 10,000 deaths as of September 1, 2021.12 These numbers are conservative and likely represent an undercount of actual deaths.13 It also doesn’t begin to account for the negative impact of social isolation from ongoing lockdowns. Nursing home residents constitute less than one percent of the population but account for a wildly disproportionate percent of California deaths from COVID-19.14 They are also human beings who deserve to be treated with respect and dignity. The pandemic has profoundly confirmed and reinforced the evidence-based literature on the impact of inadequate staffing. A University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) study in May 2020 showed nursing homes with Registered Nurse (RN) staffing under 0.75 RN hours per resident day (hprd) were twice as likely to have residents with COVID infections.15 A subsequent 2020 study by Cal Hospital Compare and UCSF found that higher total nurse staffing hours reduced nursing home residents’ COVID infection rates by half and that facilities in California with higher RN staffing reduced COVID death rates by half.16 Studies in other states have confirmed that higher RN staffing levels were associated with fewer COVID-19 outbreaks and deaths.17 Moreover, research shows that nursing homes with COVID-19 outbreaks among staff or residents were more likely to report staff shortages.18 Not surprisingly, nursing homes with higher previous RN staffing levels before the pandemic and those with higher overall quality ratings were less likely to report nursing staff shortages.19 The pandemic has given us the opportunity to more clearly comprehend the impact of not having enough staff. Within a skilled nursing facility, the medical director can be a key component to influencing the desire of staff to stay present and be clinically competent caregivers during even the worst of times. CALTCM has promoted the role of an engaged medical director. The medical director relies on frontline nursing staff as essential partners in ensuring and implementing quality. Nurses are the ones providing care 24 hours a day. RNs are the only full-time staff in a nursing home with the training to clinically assess a resident. Inadequate staffing directly affects a nursing home’s ability to prevent and contain COVID-19 in addition to other public health concerning outbreaks such as Influenza. One of CALTCM’s first recommendations at the onset of the pandemic was that all nursing homes have a full-time infection preventionist (IP). While necessary, it is not sufficient. In many ways, all staff are IPs. RNs are essential to design, implement and monitor infection control plans for facilities as well as individual resident care plans. RNs are trained in infection control, resident assessment and care planning (including for infections), and surveillance of residents (including for infections and other conditions). They are responsible for supervising licensed vocational nurses or licensed practical nurses (LVNs/LPNs) who are generally responsible for giving medications and treatments to residents. Second, even basic infection control measures—like hand washing, donning and doffing personal protective equipment (PPE), disinfection/decontamination—take time and require training for all staff. Without sufficient staff, even staff with adequate training may fail to consistently perform these basic but essential tasks given the pressure to move quickly from resident to resident. Despite evidence demonstrating the importance of nurse staffing levels, understaffing has been a longstanding problem in California nursing homes and across the country. Before the pandemic, almost 80% of California nursing homes did not meet RN staffing levels of 0.75 hprd and 55% did not meet total nursing levels of 4.1 hprd.20 These were standards that were recommended by a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) study in 2001, almost 20 years ago, when the complexity of NH residents was significantly lower.21 The nurse staffing problem is ongoing in nursing homes. In the third quarter of 2020, of the 1,147 freestanding California nursing homes reporting staffing data to CMS, 79 facilities did not have 24-hour RN coverage, 872 (76%) did not have 0.75 RN staffing hours per resident day, and 512 (45%) did not have 4.1 total nursing hours per resident day.22 The catastrophic results related to the COVID-19 pandemic speaks for itself. It’s time to utilize all the evidence-based literature to make recommendations. Federal and California State Staffing Standards Table 1 below describes the federal and California standards for how staffing needs are defined, what the minimum staffing standards are, and what requirements there are to adjust staffing for resident acuity and publicly post staffing data. This illustrates that facilities that employ enough staff to meet the minimum California requirements, do not necessarily employ adequate staff to meet their residents’ needs according to federal requirements. California standards are well below the level recommended by research studies and experts. A Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) benchmark study (2001) established the importance of having a minimum of 0.75 RN hprd, 0.55 LVN hprd and 2.8 CNA hprd, for a total of 4.1 hprd for long-stay residents to prevent harm to residents.15 A recent study reinforced the finding that 2.8 CNA hprd was a minimum level required and that based on resident acuity, CNA hprd should range between 2.8 and 3.6 hprd.23

California Staffing Waivers Health and Safety Code section 1276.65(l) required the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to develop a waiver process in response to workforce shortages. Waivers can exempt skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) from the 3.5 direct care service hours requirement and/or the 2.4 CNA hours requirement. A SNF seeking a workforce shortage waiver must submit a waiver application to CDPH pursuant to the requirements in AFL 18-16. Facilities must describe the recruitment plan to address the shortage, the facility’s recruitment efforts, current staffing, applicants, the salary offered for the position and the use of registry services, but this information is not available to the public. When staffing waivers are issued, staffing levels go below the state minimum standards and well below the standards recommended by researchers and experts. A recent study found that California nursing homes with staffing waivers in the third quarter of 2020 were significantly more likely to experience increased resident and staff COVID-19 infections and more resident deaths than facilities without waivers.24 Staffing waivers do not waive the evidence-based ramifications of inadequate staffing. As clinicians, it is incumbent upon all of us to recommend what is best for the patient. Perhaps it is time for the state to assist with developing solutions that assure adequate staffing levels rather than giving facilities permission to operate with inadequate levels of nursing staff that is associated with poorer nursing home resident outcomes. This could include but not be limited to, providing nursing staff resources, enlisting the support of military trained nurses or allowing nursing students to assist with some tasks. Low Wages and High Turnover The California nursing home workforce has been unstable for many years. The average California nursing home had over 50% nursing staff turnover in 2019.25 A recent study found that nurse staffing turnover rates of 50% or higher result in a 30% increase in COVID-19 infection rates.26 Having an adequate labor supply is definitely a major issue, but high turnover and shortages of RNs and nursing assistants have other contributing factors, such as low wages and heavy workloads.27 Nursing home RNs often work in isolation, shouldering considerable responsibility for day-to-day management and administrative tasks in addition to making clinical decisions and referrals. The average California nursing home RN wage per hour, however, was only 76% of hospital RN wages ($41.54/hour compared to $54.44/hour) in 2019.28 Nursing assistant average wages in nursing facilities were $16.75/hour in 2019, although the wages vary widely across nursing facilities and regions in California.22 The wages for nursing assistants are often lower than hospital nursing assistant wages.29 Furthermore, according to glassdoor.com, a garbage truck driver makes a minimum of $26.44/hour or $55,000 annually in an entry level position with no training. This is a $10.00 difference per hour wage compared to nursing assistants who are faced with the challenging conditions/demands of caring for vulnerable older adults. Low wages combined with heavy workloads correlate with the high incidence of work-related injuries and contribute to poor continuity and quality of care. The low wage rates also promote the continuing disparities for nursing assistants, many of whom are women, black, indigenous and people of color, and/or immigrants. This low pay leads to high proportions of nursing assistants relying on public assistance including Medicaid, food stamps, housing subsidies and tax credits. 22 Furthermore, the low wage rate encourages nurses to work multiple jobs to support a family potentially leading to transfer of infections from one facility to another. Estimates in recent research by LeadingAge state that increasing the minimum wages for CNAs by 15% per hour based on the minimum wage calculator would translate into reducing turnover and stabilizing the workforce, reducing staffing shortages, increasing the hours that individuals are willing to work, and increasing work productivity.30 Better wages should also decrease the need to work at multiple jobs and therefore decrease the risk of COVID and other transmissible infections to nursing facilities and their residents. Recommendations for California Ensure that minimum recommended staffing levels are met. Given the evidence of staffing needed to improve care delivery to residents, we recommend that all nursing homes provide nurse staffing at a minimum level of a total of 4.1 hprd, with an RN hprd of 0.75, LVN hprd of 0.55 and CNA hprd of 2.8. Reduce nursing turnover and minimize the use of waivers by ensuring adequate wages. Nursing facilities should make every effort to significantly reduce nursing turnover rates and to minimize the use of staffing waivers except in emergency situations. In order to accomplish this goal, nursing facilities should:

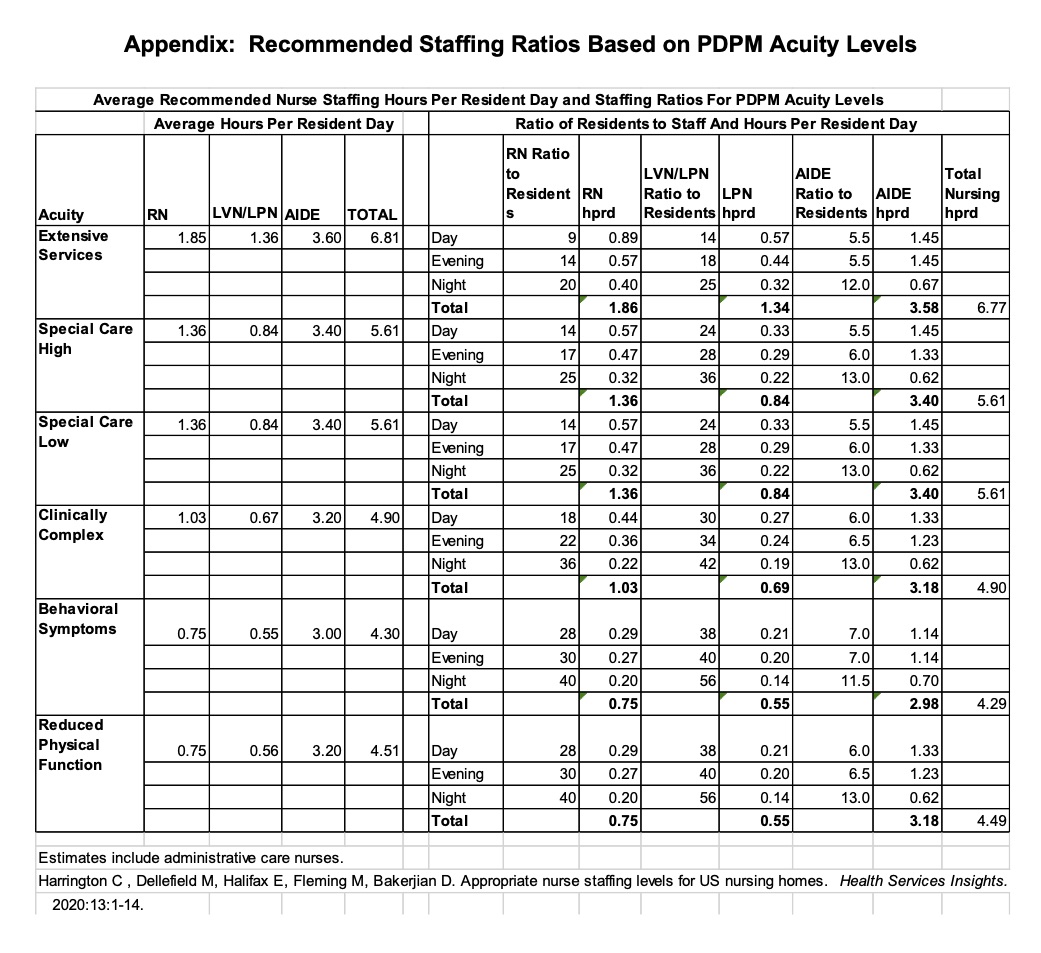

Ensure that nursing homes adjust staffing levels to meet the acuity needs of residents. Since 2019, CMS Medicare prospective payment system requires that Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessments use the Patient Driven Payment Model (PDPM).31 Resident acuity is classified into 6 basic nursing acuity levels consistent with the (PDPM) categories from highest to lowest:

These categories identify both the licensed nursing care needs and the CNA care needs. In order to meet federal nurse staffing standards, nursing homes need to identify their average resident acuity. They can do this by aggregating the PDPM nursing acuity needs of residents and dividing it by the average census. Each facility should then adjust its staffing to a level commensurate with the resident needs as recommended. Recommended staffing hours and ratios have been developed and published to guide nursing homes in addressing the average resident acuity in nursing homes.32 Conclusion The Director of Nursing and Director of Staff Development, in collaboration with an engaged, knowledgeable, and competent medical director, should determine appropriate acuity-based staffing levels in nursing homes. The evidence-based literature supports minimum staffing levels with limited exceptions, even in predominantly custodial nursing homes, due to the medical complexity of today’s residents. The exceptions should not drive staffing policy, nor should the challenging workforce shortage issues that we are facing. Policy should be based first and foremost on providing the quality care our residents deserve. Questions about the financing of appropriate staffing levels must be addressed in the context of full transparency.33 Workforce shortages cannot be a blanket excuse for allowing poor quality of care. The COVID-19 pandemic has tragically demonstrated this fact. Nurse staffing ratios need to meet the demands of acuity-based resident-centered care within a skilled nursing facility. Assuring a consensus style of leadership, including an engaged and knowledgeable medical director; improving wages and benefits; and respecting and empowering CNAs and RNs within nursing homes will reduce turnover and improve morale. Staffing shortages can also be positively impacted with changes in requirements to ease the administrative burden for each staff member and enhance the satisfaction of caregiving for vulnerable older adults. Finally, with the stark impact of these issues in nursing homes with a high percentage of residents of color, we believe that staffing requirements should immediately be focused on these facilities. We close this White Paper by reinforcing the call to action in our opening paragraph. While additional studies may help clarify and focus our precise definitions of minimum staffing levels, and while calling for minimum levels cannot alone solve the staffing crisis, we must act now to ensure adequate staffing of our nursing homes. The current combination of inadequate staffing and disparities can only lead to more tragic situations and outcomes. Endnotes

Appendix: Recommended Staffing Ratios Based on PDPM Acuity Levels |