| Diagnosing and Treating Depression in the Elderly |

|

by Vanessa Mandal, MD The IOM (Institute of Medicine), now called the National Academy of Medicine, defines patient-centered care as: “Providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”1This principle can be applied to the management of depression in geriatrics. Dr. Jay Luxenberg gave a comprehensive overview of diagnosing depression and subsyndromal depression in the elderly, with focus on DSM-V criteria and applicable ICD-10 diagnostic codes. Not all post-acute and long-term care facilities have consulting psychiatry services available on-site. It is incumbent on physicians to develop competence in diagnosing depression and differentiating from grief reactions and social isolation. The PHQ-9 is a valuable tool and is already included in all nursing homes’ Minimum Data Set information. PHQ-9© Total Severity Score can be used to track changes in severity over time2 and can be interpreted as follows: 1-4: minimal depression

5-9: mild depression

10-14: moderate depression

15-19: moderately severe depression

20-27: severe depression (20-30 for PHQ-9-OV©)2

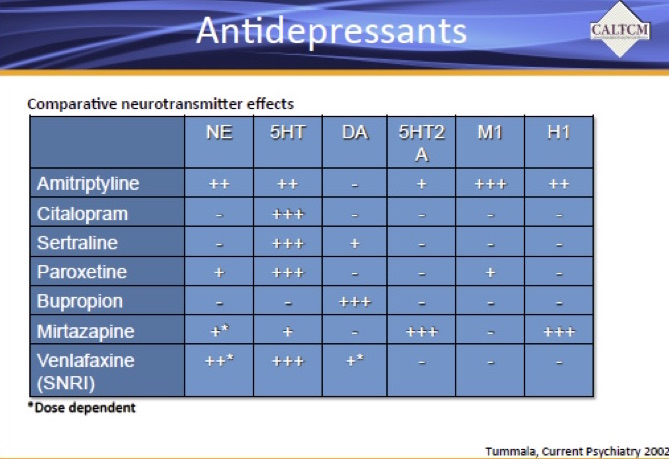

As in the case of managing hypertension, treatment of depression entails knowledge of comorbid conditions, medications, potential drug interactions and previous treatment regimen. Dr. Glen Xiong presented information on the various types of medication used for treating depression, determining when augmentation is needed and assessing for gradual dose reduction. Basic principles outlined were: use behavioral and supportive measures when possible, verify adherence to regimen, start low, and titrate slowly to effective dose. Antidepressants can be selected based on the desired neurotransmitter effects:

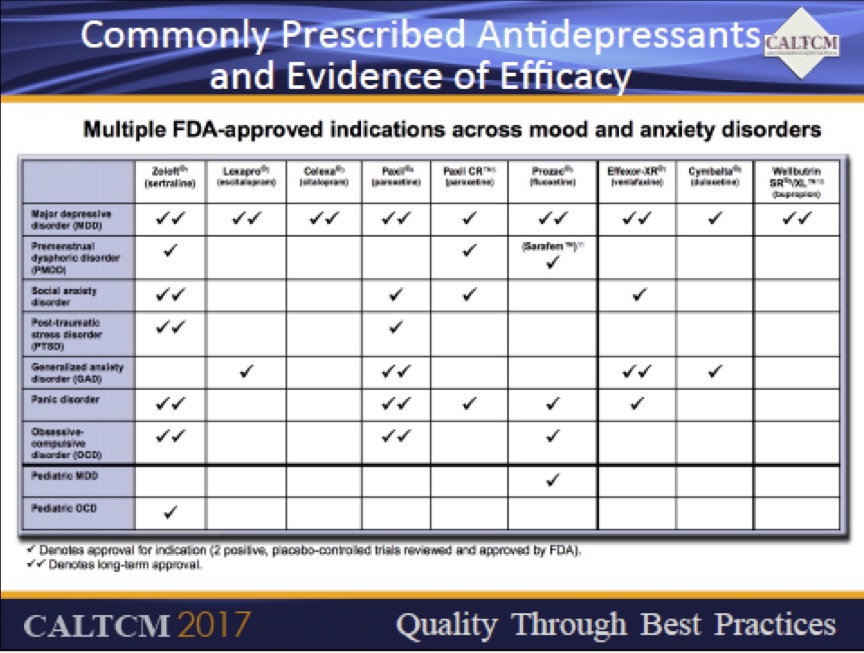

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have unique profiles. Sertraline blocks reuptake of serotonin and dopamine, and has relatively low risk for drug interactions. It may cause akathisia, diarrhea, constipation and decreased libido. Citalopram and escitalopram also have low risk for drug interactions, but carry QTc prolongation warning at dose more than 40 mg, with recommended maximum dose of 20 mg daily in patients over 60. Caution is necessary when using citalopram or escitalopram with other medications that prolong QT interval. Fluoxetine has a long half-life, and is ideal for intermittently compliant patients. Paroxetine has high anticholinergic and antihistamine side effect profile and can cause dry mouth, sedation and weight gain. It has a short half-life and a high chance for drug interactions, best avoided in the elderly. SIADH, risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and risk of falls are potential side effects of SSRIs. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) include desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine. Desvenlafaxine has a short half-life with more risk for discontinuation syndrome, can cause elevated blood pressure, and does not cause sedation. Venlafaxine has similar profile as desvenlafaxine, can be used as an adjunct for chronic pain, can cause elevated blood pressure and heart rate. Both of these require dose reduction with renal insufficiency. Duloxetine is unique in that it is also FDA approved for fibromyalgia and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Bupropion is available in three formulations. Short-acting bupropion is administered twice a day and has dual action on dopamine and norepinephrine receptors. It is contraindicated in seizure and eating disorders. Bupropion XL can increase risk of seizures in those with alcohol withdrawal, may worsen anxiety associated with depression, and slower release is supposed to lower side effect profile. There are no data to support its use in anxiety disorders. Mirtazapine increases central serotonin and norepinephrine activity, has less effects on libido, causes increased sedation at lower doses less than 15mg, may be helpful for anxiety disorders, can cause weight gain (not always an adverse effect in the nursing home population), and can cause leukopenia. Medical comorbidities should be considered when choosing antidepressant therapy. Duloxetine and venlafaxine can be used in patients with neuropathic pain. Mirtazapine may be better for patients with weight loss and insomnia. Paroxetine or duloxetine can help for fibromyalgia. Bupropion would be useful in smoking cessation. Side effect profile should also be a major determinant in medication selection.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are more risky in older patients due to anticholinergic effects, which can aggravate glaucoma, constipation, urinary retention and confusion. They may also cause antiadrenergic induced postural hypotension, antihistaminic sedation and risk of falls. In summary, the PHQ-9 is a useful tool for diagnosing depression. Once diagnosed, the treatment plan should encompass non-pharmacological and pharmacologic measures. Medication choice must entail familiarity with the mechanism of action of the antidepressants, their side effect profile, and the potential for adverse drug event, the potential interactions, and the comorbid illnesses of the patient. 1. The 8 Principles of Patient-Centered Care-One view Healthcare www.oneviewhealthcare.com/the-eight-principles-of-patient-centered-care/ 2. PHQ-9 Total Severity Score. CMS’s RAI Version 3.0 Manual

|